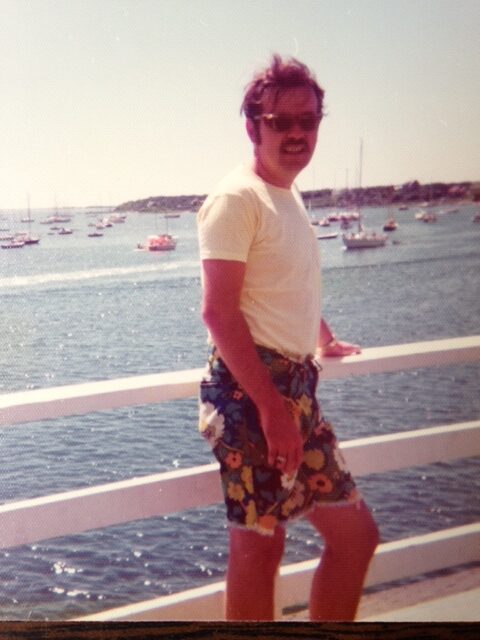

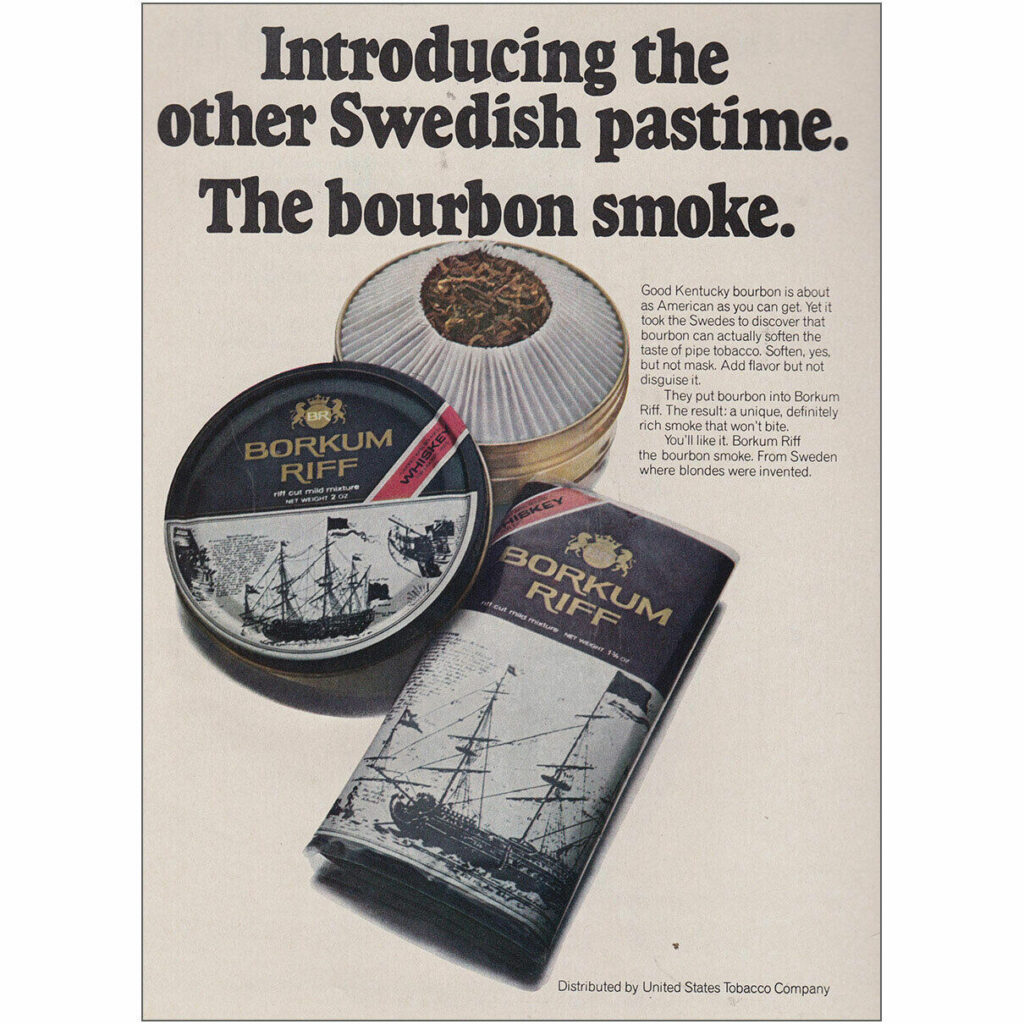

Anyone who knew me back in the day will recall that the scent of tobacco smoke was part of the Murphy household; Pops grew up a smoker, as was expected of a young Irish Catholic in Boston, circa 1950-something, and had quit the cancer sticks before I was born, and the pipe served as replacement/coping device until he was big enough to dispense with that in the mid ’80s (his father, our beloved Gramps, smoked happily into his ninth decade). My association with his pipe is totally positive, and the imagined scent of Borkum Riff is the olfactory soundtrack of a less complicated time. Huge gratitude, once again, to The Good Men Project for publishing more of my work, and a big shout out to the fathers everywhere who kept it real for the kids. (Link to these two and all the previous poems here.)

An Ode to Borkum Riff Tobacco

My old man drank Scotch rocks w/ a splash,

only on weekends, his Catholic sensibilities

ensuring he didn’t imbibe on weeknights:

Budweiser did the heavy lifting in our house,

a beer proving Germany and America could

come together in the name of, if not peace

and prosperity, a contingency to celebrate—

alone or any occasion—like living in the ‘70s.

My grandparent’s house, older than they were,

acquired certain scents the way most things do—

a peculiar combination of routine and repetition:

the smell of pipe tobacco and raw meat and blood

from home births, blended with the dying memories

of old traditions being supplanted by whatever it is

money affords, or religion allows, when we’re able

to find distraction from the business of being alive.

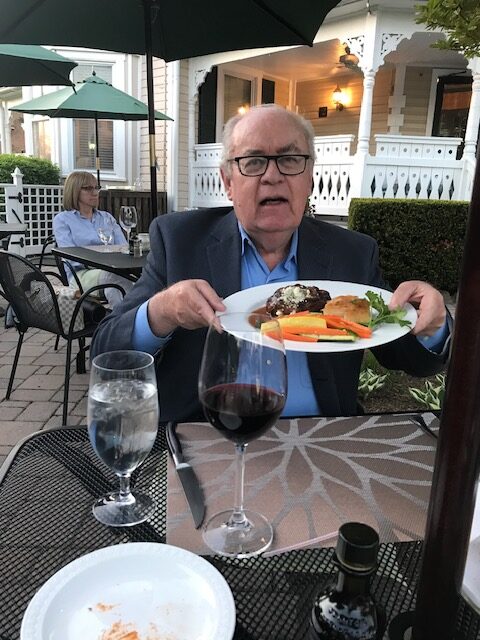

Dinner at My Old Man’s Favorite Old School Restaurant

In this place jackets and ties are not required, but they’re certainly welcome: less dress codeand more reminder that a certain sensibility—from an era that made much more sense, while no longer prevalent—will still resurface at times. This remains a venue for meals that seek to elevate whatever occasion: a proposal or birthday, an anniversary or after a funeral, group function or, say, standing celebration, the import of which is known only to the father and his son, who, in a gesture at once ritual and respectable, picks up the tab now, overdue karmic installments. The server, in a tux seemingly tattooed on, rolls out the mostly-cooked meal, tableside theater with a contraption equal parts Bunsen burner & old school hot plate—a routine managing to be at once ridiculous and aristocratic; formality making everyone involved feel more important: meat and potatoes with fresh Béarnaise, dispensed like we’ve won the condiment lottery; the only way this whole set piece could be less stolen from the ‘70s is if Tony Manero danced it out in a polyester suit, Bee Gees blasting, in translation, ochevidno; that these overpriced entrées are unexceptional almost beside the point: this whole ceremony, from vodka aperitif to five thousand calorie dessert an unimprovable rite; a family affair—ourselves and the stoic folks servingus—a starched staff too busy actively hating each other to quibble over minor slights, every penny earned put into the proverbial (or possibly actual) pot; each time a customer says check please confirmation there’s one way to live, one transaction at a time, all while we stuff ourselves with foodstuffs, imitating scenes from novels that hoped to invoke extravagance from an earlier century—the meat, spirits, and spectacle superfluous, all this industry a reminder to make memories and, for a few hours, place our thoughts outside time, at once aware of and oblivious to what that our ancestors fought and died to accommodate.