What can be added to the mostly excellent obits and tributes coming in from around the globe, including shout outs from all-time heavyweight champs like Paul McCartney and Bruce Springsteen? Not much. Brian Wilson was beloved by most and worshipped by the types of musicians many worship: he’s an Alpha in every sense when we talk about American music and the formation of a distinct CA cultural aesthetic.

I was always a fan (because duh); I loved–and grew bored with many of–the big hits, I discovered ‘Pet Sounds’ down the road, and then rediscovered it later when I was ready for it (and could appreciate the ways it impacted The Beatles’ development and that brief, beautiful one-upmanship that changed pop music, permanently). I seldom listen to it start to finish but like other iconic albums (I think of R.E.M.’s ‘Murmur’ or Love’s ‘Forever Changes’), there are certain songs so indelible, so ceaselessly glorious they can be enjoyed any time, all the time. They are those magic spells that make life way more worth living.

So I was good. I knew Brian Wilson loomed large, had entirely earned his late-in-life victory tour after decades of desolation and disillusion, and there were so many The Beach Boys songs I could always call on. But then, in late 2011, the much-discussed ‘Smile Sessions’ dropped. For music nerds, this was like the Lost Ark or the Dead Sea Scrolls, or a lost Herman Melville manuscript; a miracle many of us had assumed & accepted we’d never hear b/c it wasn’t meant to be. Put simply, it’s impossible to explain the impact of this revelation (and allow me to be a minority voice expressing the unpopular opinion that Wilson’s triumphant reclamation of this project in 2004 was…..aight. I think much of the approbation was from starved fans who wanted something/anything after so many years of rumors and misgivings).

The ‘Smile Sessions’ was, and I don’t say this lightly, like ardent fans of The Beatles hearing ‘The White Album’ if it had never seen the light of day, or huge fans of Jimi Hendrix suddenly hearing ‘Electric Ladyland’ ….or classical music fans having Mozart’s 40th or Ludwig van Beethoven’s 9th dropped….out of nowhere. It was THAT unexpected, welcome, miraculous. Cliche alert but I *literally* couldn’t believe my ears as I listened, and I’m thrilled to report that combination of delight & disbelief remains a decade and a half later: I CANNOT BELIEVE how great this music is. So much so it demands an entire re-evaluation of 1966/1967 and how we understand that seminal period, that entire decade, and everything that followed.

I had the opportunity to write about this and I seized it like a starved exile. I spent a good chunk of late summer 2012 *living* in this release, luxuriating in those sounds, and trying to make sense of it, celebrate it, and tell the sad, awesome, redemptory story of Brian Wilson and ‘SMiLE’–at once the most depressing, infuriating, and glorious story in pop music (artistic?) annals. That’s my story and I’m stuck to it. The entire review (it’s long) is in the comments and it’s a piece I remain deeply proud of. I offer it up as the best way I can think to celebrate the remarkable life of Brian Wilson. RIP.

There’s a sad irony to Sly Stone and Brian Wilson, arguably two busts belonging on any American songwriting Mount Rushmore, dying within days of each other. It would be difficult to find two more brave and visionary artists who suffered greatly for their gifts. Two creative geniuses that managed to extract every ounce of inspiration and vision, maximizing their talents in literally unbelievable ways, and did so in the service of a catalog that ranks among the most ebullient, irresistible, life-affirming in all music. It serves to illustrate the enigmatic nature of art, but also our capacity, as human beings, to move the entire world in a better direction. Is there anything more noble, and heroic than this?

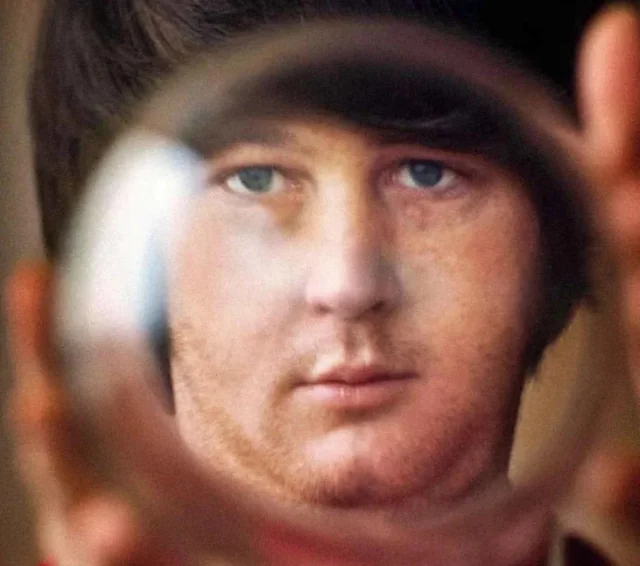

As most folks know, Brian Wilson was, as the expression goes, a tortured soul. A sensitive, gentle, fragile soul. Driven, ambitious, filled with inspiration he could scarcely contain. Granted, The Beach Boys prime was during an era when bands put out an album per year and toured ceaselessly. But Brian was extra, as the expression goes. Like Paul McCartney, his only real peer (I guess we can throw Dylan into the mix, on principle) during that decade in terms of pound for pound productivity + brilliance, he just oozed talent, and the music flowed like, well, a succession of clean, clear waves.

Let’s get this out of the way right up front for any naysayers, naive newcomers, or those who think (albeit understandably) that the hype is always heavier than the reality. In this instance, we can—as we might with few others including a short list that includes, of course, the aforementioned Sly Stone and McCartney, add John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix—there should never be the slightest controversy or hesitation in declaring Brian Wilson a Genius with a capital G. More: he wasn’t merely one of the most insanely talented musicians, he really did have that Mozart thing going on (if you’ve seen Amadeus, you know what I’m invoking) where he heard it all, and the only struggle was getting the right people to perform all the notes he had in his teeming mind. Put another way, Wilson wasn’t merely God, he was also all the angels singing in their celestial choir.

As I did with Sly, I’m satisfied that most of the official obits and appreciations will capture the salient points: the hits, the highs, the decline and redemption. I’ve always (aside from the music, which ultimately is all that matters; all anyone should concern themselves with) been more intrigued by the lows, the ways Wilson turned strife, resistance, and pain into bliss. He was done dirty by the people who should have protected him (starting with his sadistic father), and if you’ve ever seen any interview, you can see that complete lack of guile, the genuinely childlike affect, the innocence and grace. He was humble, but this was in no small part because the world humbled him, repeatedly.

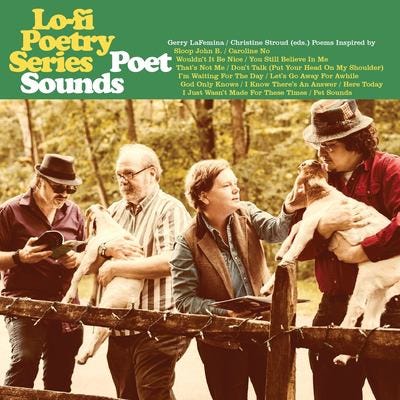

I was invited to contribute a poem to a super cool project, and it was my honor to do so. The anthology, Poet Sounds (I know, right?), is a…well, poetic celebration of all-things Beach Boys. I took it as a welcome if daunting challenge to—kind of like I’ve done with Sly Stone and many of the musicians I’ve featured in my Blackened Blues project—compress an entire bio into something that can stand as equal parts tribute, cultural commentary, and personal statement. My poem, Only Gods Know, is below (and also appears as “Brian Wilson’s Ear” in my collection Rhapsodies in Blue).

Brian Wilson’s Ear*

(During his childhood, Wilson was hit in the head with a lead pipe, resulting in the near-total loss of hearing in his right ear (his abusive father had his own ear damaged, courtesy of a lead pipe swung by his abusive father). Wilson has credited the impairment with allowing him to “hear” differently, helping him translate the sounds in his head into songs.)

Your old man made you and then tried

to end you, the oldest story in the book.

He knew those ancient myths, immortal

through stories lost and gone, all about

Heroes & Villains. Kronos knew the score:

Father is the child of the man. They’ll try to

kill you or else become you—so arrest that

development and swallow each one-two-three,

absorb and keep everything inside the family.

Achilles in California, head buried in the sand,

a son willed to success, out of tune but blessed

with an attenuated ear—molded in trials by fire

or more banal brutalities: a 2×4 or fists or worse,

words. Reborn in the salty wake with everything

you couldn’t hear and all you could: harmonies

from heaven, the mysteries within Adam’s apple—

a towering babble your own brothers didn’t divine,

leaving a wrecking crew to launch a thousand songs…

(And wasn’t Noah simply obeying orders? Surf’s up:

Bad vibrations flooding a sinful earth, his sloop one

big barnyard catching a wave on top of the world?)

Your own symphony to God: wouldn’t it be nice?

Bringing down the walls with the sound of a Smile.

Hang on to your ego! Arrogant Icarus, he fucked

with the formula, flying too close to the source, got

burned; or Sisyphus with his Endless Summer, or

Samson, whose prayers buried him in rolling stones?

A half-crazy conductor (for the record), Fate finds you

consigned to a sandbox, bearded and full-bellied,

a god in decline, ill-advised and alone—a castaway.

5/16/66.

A day that changed music, forever, for the better.

A case could, and probably should, be made that we ought to refer to rock music as “BP” and “AP” (Before Pet Sounds and After Pet Sounds).

Wouldn’t It Be Nice. Talk about an opening statement, and statement of purpose. This is the sound of a revolution.

And then it’s a succession of brilliance, one miniature pop-opera at a time. It’s the sound of Brian Wilson maturing and growing into his genius. Not for nothing did Paul McCartney hear this and know he had to up his (already considerable, and all but peerless) game.

Brian Wilson was perfecting a somewhat unprecedented type of songwriting here: upbeat (sounding) but reflective, almost pensive ballads. No question The Beatles were listening closely to songs like “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head On My Shoulder)” and “That’s Not Me” (see: Mac’s songs on the subsequent Revolver).

Whimsy, possibly enhanced by the ingestion of some consciousness-expanding substances, resulted in songs that are equal parts silly and audacious. It’s hard to imagine Beefheart and Syd Barrett having the balls, or ability, to take their next steps without a song like “Sloop John B”. It is disarmingly simple, but not simplistic. If nothing else, the arrangement is a delivery device for those voices: Wilson (as the image on the back cover, copied above, illustrates) was pushing himself, and his mates, to blend their vocals in increasingly complex and ingenious harmonies.

Possibly the most important track (at least to Paul McCartney) is the epic “God Only Knows”. Rather than attempt to articulate its import, I’ll let Mac do the honors:

“It’s a really, really great song—it’s a big favorite of mine. I was asked recently to give my top ten favorite songs for a Japanese radio station…I didn’t think long and hard on it, but I popped that [“God Only Knows”] on the top of my list. [Thinks for a moment] It’s very deep. [Quotes the lyrics to “God Only Knows”] Very emotional, always a bit of a choker for me, that one. There are certain songs that just hit home with me, and they’re the strangest collection of songs…but that is high on the list, I must say.”

More from Macca on Pet Sounds, HERE.

Speaking only for myself, I love Pet Sounds and appreciate its place as perhaps the single-most important stepping stone for the year (’67) where pop became art (a LOT more on that HERE). For me, Pet Sounds is like Sgt. Pepper in that I seldom listen to it all the way through the way I can later albums I prefer (think SMiLE or Abbey Road—more on the latter HERE). And like Sgt. Pepper, there are a handful of songs that I can listen to repeatedly, anytime, and never grow bored or uninspired. The number one example is “Hang On To Your Ego” (which became “I Know There’s an Answer”, allegedly based on Mike Love’s concerns that the lyrics were too blatantly LSD-inspired. Love must be acknowledged, if nothing else, for being the anti-Wilson in virtually every regard). Which one is better? Personally, I’ll take both.

Even an ostensibly throwaway lark like “Little Pad” manages to disorient and delight in equal measure. And while it’s so obviously (and awesomely) of its time, you listen to this and you’re hearing the future. I hear everything from Fleet Foxes and Grizzly Bear to Sufjan Stevens and Sam Beam (Iron & Wine), and the ways Mike Patton & Co. appropriated The Beach Boys on Californiaare sublime bordering on ridiculous. The list truly goes on (and on) but it would be remiss to not make special note of the Zombies masterpiece Odessey and Oracle (which, like SMiLE, remains name-checked by the most important people but way under appreciated) would be unimaginable without Brian Wilson’s use of melody and vocal harmonies.

Speaking of SMiLE, I spent a decent chunk of the late summer 2012 going deep on the release of the incendiary, instantly immortal collection The SMiLE Sessions. There are a relative handful of albums so meaningful and personally significant that I almost dared not tackle them, for fear of not doing them justice (on that list, off the top of my head, I include The Who’s Quadrophenia, Charles Mingus’s Ah Um, and the entire catalogs of Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, and Pink Floyd.)

I’m proud to say this is one of my favorite pieces of criticism, and I include it in its entirety, below.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Icarus soars too close to the sun. Othello, vulnerable and halfway crazy, mistakenly trusts the evil Iago. The product of a celebrated cultural era sets out to fictionalize some of the forces that made his ascent—and disintegration—possible (hint: he is the same author who opined there are no second acts in American lives). The captain of a sinking ship, obsessed unto madness by a malevolent mammal, takes his crew with him under the water into oblivion. A small man, armed only with a sling-shot, takes aim and slays the giant. The underdog gets off the mat to dethrone the champion, the nerd flies out of a phone booth, the orphan slides a magic slipper on her foot, a kid who would be king pulls the sword from the stone…

Get the picture? All of these elements are, to varying extents, contained within this epic Tragedy that detours into Comedy and ends up as Romance. And the rest is History: the construction, dissolution and redemption of one man’s very American Dream.

Speaking of America and dreams, there’s one overriding rule. We want our artists to earn it, to mean it, and sometimes the world sees to it that they suffer. If any single artist left it all, every scrap of his ambition and energy, on the table, it’s Brian Wilson. He did not pay the ultimate price; he did not die. But for an unconscionable number of years—and years that got broken into months into weeks into hours into minutes into seconds like all the grains in a sandbox—Wilson had to reconcile himself to what must have seemed an irreconcilable verdict: a senseless world declared that he was insane. And then, having to live with a failure only he could be accountable for, even if blame could fairly be laid at the rubber souls of almost everyone that surrounded him.

For anyone new to the story, or unfamiliar with the intricacies therein, it might be useful to summarize what has long been rock and roll’s ultimate cautionary tale. There was this band called The Beach Boys and they crafted best-selling pop confections about cars, surfing and girls. Driven by the increasingly determined—and restless—frontman, the group dropped Pet Sounds on a mostly unprepared world. How influential was it? Paul McCartney who, at that time, brooked competition from no other mortal not named John Lennon, was intimidated, and ultimately inspired by what he heard. In typical Fab Four fashion, he and his mates rose to the challenge and first Revolver, then Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band followed. Of course, Pet Sounds was not a commercial success, at least compared with previous number-one-with-a-bullet efforts from admittedly less complicated times. This did not sit well with some of Wilson’s sidemen, particularly the Kiddie-Pool deep Mike Love.

When “Good Vibrations” dominated the charts in late ’66, it was a gauntlet thrown as much as a premonition of greater things to come. The Beatles got there first and Sgt. Pepper became the undisputed artistic and cultural event of 1967. SMiLE, initially—and tellingly—entitled Dumb Angel, was supposed to be the Beach Boys’ counterpunch. Impossible as it might be to imagine, Brian Wilson was poised to share the stage with Lennon/McCartney. It doesn’t compute to contemporary minds because decades of blank space and unfulfilled promise did what history always does: vindicate the winners. But Wilson, as much as his peers across the pond, was edging the idiom toward the avant-garde, and the arresting results of “Good Vibrations” could be seen as an opening salvo. SMiLE, then, was going to be the band’s masterpiece, and possibly the crown jewel of the Summer of Love. It very well might have put The Beach Boys, not The Beatles, on the top shelf critically as well as commercially.

But it wasn’t meant to be. Wilson lost first the goodwill and support of his brethren and then, his mind. (Not unlike the other sad casualty of ’67, Syd Barrett: it was an escalating intake of drugs—especially the LSD he credited with unlocking the doors and assisting the great visions— that accelerated his southward spiral.) And so, the work in progress was mostly scrapped and the shell-shocked group cobbled together the odd, occasionally sublime—if ultimately underwhelming—replacement, Smiley Smile. In the ensuing decades those aborted sessions—the strange fruits of Wilson’s measureless mind—became rock music’s Holy Grail. The material simply could not find the light of day; Wilson was too far gone and the results allegedly too impenetrable for public release.

And now, in a real-life Deus ex machina, rock’s scariest horror story has been transformed into pop music’s Dead Sea Scrolls. Salvaged from oblivion with the blessing—and assistance—of the man who made them, in late 2011 we received the opportunity to hear them, in full (or as full as we can reasonably hope) for the first time. The results must be considered as close to an unvarnished approximation as possible of Wilson’s original vision, and they are miraculous. Like a bombed and burned-out cathedral, there is dirt and dust aplenty, and the stained glass is, in places, broken and filled with cobwebs and strange empty spaces. This dirty authenticity only adds layers of meaning to the overall impact.

First reaction: it’s difficult, bordering on unreasonable to believe the current incarnation of SMiLE—modeled as it is after Wilson’s crucial but now less significant Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE from 2004—is comprised mostly of uncompleted drafts, bits and pieces. It sounds that great; it feels that complete.

Second reaction: I kept finding myself thinking much less of Sgt. Pepper and more of two later Beatles works, The Beatles (White Album) and Abbey Road. It’s all in here, and where The White Album is a glorious, murky mess, these SMiLE sessions are more like wave after wave crashing onto soft sand. There are moments that conjure the acoustic bliss of “Julia” and “Mother Nature’s Son”, the surreal parlor music of “Martha My Dear” and “Don’t Pass Me By”, the baroque touches of “Long, Long, Long” and “Good Night” and the kitchen sink chaos of “Wild Honey Pie” and (of course) “Revolution 9”. And where Lennon/McCartney got some wonderfully satirical licks on topical—and enduring—American history via “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” and “Rocky Raccoon”, Wilson was clearly attempting to tackle the whole mythical cycle of westward expansion. As such, SMiLE might be best understood, or appreciated as a psychedelic tour of forward motion, incorporating sounds and sights (and smells and tastes) invoking myriad aspects of Americana. We are treated to chanting, cowboy movie theme music, field studies ranging from Indian to Hawaiian, cool-ish jazz, tone poems with classical elements, cartoonish sound effects, Musique concrete and a yodel thrown in for good measure. And most of all, tons and tons of the best harmonizing you’ve (never) heard, until now.

To me, and I’ve written about it, the high-water mark of harmonizing, with due respect to Simon and Garfunkel, Crosby Stills and Nash and even earlier Beach Boys material, remains Abbey Road (and it’s still astonishing to consider the trajectory The Beatles took, starting with the glistening sheen of the early hits to the mano-a-mano glory of Rubber Soul to the all-in, panoramic sweep of their final work). All that notwithstanding, I’m unsure I’ve heard anything approaching what is happening, on a purely vocal level, throughout SMiLE. It is instructive here to note the bonus tracks, particularly the “SMiLE Backing Vocals Montage”, which make it abundantly obvious how these sounds were stacked, shuffled and overlaid to create miniature symphonies of human voice. To hear these efforts come to fruition in songs as radically different as “Wonderful” (the aforementioned yodel, along with harmonies to rival Side Two of Abbey Road), “Do You Like Worms” (the previously described faux-Hawaiian chanting) or the pinnacle of harmonies and emotion in “Wind Chimes” (of which more, shortly).

One can—and should—recognize that, beginning with Revolver, The Beatles had the inclination, and money, to spend as much time in the studio as they saw fit, tinkering and tailoring until they were satisfied. They also, for understandable and well-documented reasons, had collectively grown weary of touring. Wilson too, had no stomach for the hustle and grind, even in the better days, but of course his band mates did (and still do). For the undeniable advancements of Revolver and Sgt. Pepper, Lennon and McCartney enjoyed a mutual focus and solidarity, not to mention the quite capable services of Harrison, Starr and the invaluable George Martin. Wilson, by comparison, was trying to hit a grand slam with no one else on base—or on board (and he just about knocked it out of the ballpark before a Tempest blew in and suspended play for almost a half-century). Needless to say, unlike the environment in the Beatles’ camp, the SMiLE sessions comprised the inevitable tension of a band following the unsteady lead of its eccentric yet brilliant conductor, with one eye on The Road and all this entailed: adoring crowds, fat wallets and the safety of hit singles.

“Don’t fuck with the formula,” Mike Love supposedly complained as the material grew too complicated—and unconventional—for his liking. Love’s words, and the attitude that prompted them, serve not only as a succinct summary of the internal forces Wilson found himself confronting (even in an increasingly fragile state of mind he was still the de-facto leader and resident visionary, something Syd Barrett abruptly ceased to be well before his eventual ouster), but also represents the rapacious imperatives of any commercial enterprise: keep it simple, appeal to as many people as possible and above all, never leave any opportunity for money on the table.

That Wilson lost this battle, ostensibly a victim of his own excesses and weakness, says a great deal about the ugly side of the unbridled ‘60s. Like Syd Barrett and too many anonymous psychedelic foot soldiers to count, LSD was a major incentive for creativity and expansion, but it carried a cost. By Wilson’s own reckoning, acid played an essential role in his stylistic and compositional progression, but it also hastened some of the off-kilter internal mechanisms that preyed on his confidence, if not his ability to cope. The already controversial and clownish Mike Love comes off worse than ever the more one thinks about these circumstances and what was at stake in late ’66 and early ’67. Shouting not-so-sweet nothings in Wilson’s ear would be unfortunate enough coming from a record company executive; coming from a fellow band mate, especially one who had gained a great deal more fame and wealth than he ever could have done on his own, is unforgivable.

What has tended to get lost or forgotten in the shuffle of sensationalistic trivia is that Wilson did not go down without a hell of a fight. He may not even have gone down at all so much as he was forced down, which makes the proceedings Tragic with a capital T. There can be no doubt that a primary instigating factor in Wilson’s meltdown was his utter lack of guile. Remember, the Beach Boys were square. Wilson forced them, through a combination of will and his own curious brand of genius, to be successful. They were always more than a little corny, and that formula worked on the clean-cut, if innocuous early singles. SMiLE illustrates the struggle of a naïve but proficient artist chasing the white whale inside his own head. He was making it up as he went along and just about nobody was along for the ride. Much of this can be more easily understood by hearing the numerous takes of the eventual tour de force “Heroes and Villains.” He knew what he was after, and he convinced, cajoled and begged his compatriots to cross the finish line. The results more than validate his obsessive effort: the song is masterful, complex but accessible, intense but assured, the fully realized vision of a unique talent.

So where does that leave us? Assuming that SMiLE is superior, ultimately, to Pet Sounds, how profoundly does its belated release shift of perceptions of the ‘60s; of rock and roll history? First, in what ways does it alter our well-ingrained admiration of Pet Sounds? It shouldn’t, necessarily. Put simply, just as everyone is, correctly, comfortable with The Beatles having several albums represented in what we acknowledge as the upper echelon (think Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, White Album, Abbey Road, which typically land in the Top 20, if not Top 10, of critical lists), SMiLE must correspondingly assume its overdue but welcome place in the pantheon.

Now, the fun begins. Where does it go? Is it better than Pet Sounds? In terms of ambition, scope and execution, this writer has no problem putting it at the top of the heap. And, the unthinkable: is it better than Sgt. Pepper? Yes. More influential? Obviously not. More popular? Not even close. More important to the band’s development? Hardly, since unlike The Beatles, The Beach Boys retreated, getting back to where they once belonged. But taking it on a song-by-song basis, is it superior? Unquestionably.

Now, the real fun: not much can stand alongside “With a Little Help From My Friends” and “A Day in the Life”. You can even throw in “She’s Leaving Home” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” if you must. Can even those four stand comfortably alongside “Heroes and Villains”, “Surf’s Up”, “Cabin Essence” and—take your pick—“Do You Like Worms” or “Vega-Tables”? We can leave aside “Good Vibrations” to accompany “Strawberry Fields Forever”, both released as singles in ’66. It could even be conceded that, based on the above, The Beatles best songs edge out whichever ones we can throw up against them. But, as is the case with most classic albums, it’s the odds and sods that make the ultimate case for greatness. Consider the opening salvo of “Our Prayer”, and remember Wilson remarked that his desire was to write a “teenage symphony to God”. The creepy acid-washed “You Are My Sunshine”; the gorgeous segue of “Look (Song for Children)” into “Child is the Father of the Man”; the quirky, Zappa-esque romp of “Holidays”; the pre-Abbey Road majesty of “Wonderful”; the Beatles-meet-Beefheart “The Elements: Fire (Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow)”; the presciently prog-rock “Love To Say Dada”.

And, above all, the dark gem of the lot, “Wind Chimes”. This, more than anything else The Beach Boys did (and only Love and The Doors came close, or tried), seems to provide the until-now unheard and definitive counterpunch to the phoned-in feel-good anthem that did dominate the summer of ’67, “All You Need is Love”. Calculated if not entirely cynical, “All You Need is Love” is LSD-Lite, the calm before the White Album aftermath. As a complete and consistent artistic statement, only Love’s Forever Changes (similarly embellished as it is with horns, strings, and harpsichord, with harmonies and a sense of dread lurking around every other note, occasionally threatening to move in and suffocate everything) presages the ugliness around the corner like “Wind Chimes” does—and it does so with a feeling and lack of self-consciousness that seems all the more remarkable, today. Perhaps Syd Barrett’s “Jugband Blues” delineates the harrowing descent, breaking down in real time, better than anything else. “Wind Chimes” splits the difference, and does so with the benefit of Wilson’s inimitable combination of innocence, wonder and frailty.

What results is a product that defies anything any hipster or detractor—of any generation—can credibly dismiss. SMiLE is earnest, it is honest and it is almost entirely unique. Its arrival explodes, or at least expands, the already rich narrative of 1967. It is at once the story of what was and what could have been. The question could be asked: does it represent what should have been? Probably not. Maybe the world would not have been ready for this. Maybe SMiLE would have come out and been laughed off the shelves. Maybe music would not have changed (for better, for worse) if this enigmatic masterpiece had been able to go toe-to-toe, a musical rumble in the jungle, with Sgt. Pepper. The only answer is that we can never know.

There is undeniably a cognitive dissonance listening to this, trying to make sense of it, all these years later. As awkward, or uncomfortable, or awe-inspiring as it is to hear 1966 with today’s ears, it cannot be overlooked—attention must be paid. Assessing SMiLE and giving it its deferred due need not detract from everything The Beatles are worshipped for doing. This is, nevertheless, paradigm-shattering stuff, and most welcome to honest and open minds. How often does an artifact come along that radically disrupts, and reconfigures, an established understanding of history? How exceedingly seldom does this happen, if it ever does? It has happened here and everyone has reason to be very happy it did.

In the final analysis, the vision that sustained SMiLE was undeniable; delicate yet capable of withstanding an uninterested world—which is pretty much precisely what happened. The music, this beauty, bears witness to a dream—at times dark yet always unadulterated—and it remains Wilson’s, and our, triumph.