It seems specious, even disingenuous, to suggest that a well-known, best-selling author is both underrated and insufficiently read. As it happens, Barbara Ehrenreich, one of the most informed and important storytellers of our time, managed to write books that helped change the world (for the better), but, in part because of what she wrote about, should be read by millions more, and assigned reading in any undergraduate curriculum.

From the New York Times obit:

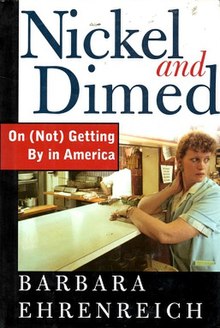

Working as a waitress near Key West, Fla., in her reporting for “Nickel and Dimed,” Ms. Ehrenreich quickly found that it took two jobs to make ends meet. After repeating her journalistic experiment in other places as a hotel housekeeper, cleaning lady, nursing home aide and Wal-Mart associate, she still found it nearly impossible to subsist on an average of $7 an hour.

Every job takes skill and intelligence, she concluded, and should be paid accordingly.

One of more than 20 books written by Ms. Ehrenreich, “Nickel and Dimed” bolstered the movement for higher wages just as the consequences of the dot-com bubble snaked through the economy in 2001.

“Many people praised me for my bravery for having done this — to which I could only say: Millions of people do this kind of work every day for their entire lives — haven’t you noticed them?” she said in 2018 in an acceptance speech after receiving the Erasmus Prize, given to a person or institution that has made an exceptional contribution to the humanities, the social sciences or the arts.

Ms. Ehrenreich noticed those millions throughout a writing career in which she tackled a variety of themes: the myth of the American dream, the labor market, health care, poverty and women’s rights. Her motivation came from a desire to shed light on ordinary people as well as the “overlooked and the forgotten,” her editor, Sara Bershtel, said in an email.

More about a seminal piece of American journalism, here.

Simply put, it’s writing like Ehrenreich’s that serves as the best antidote to ideology, and is the main reason the incurious or cynical or opportunistic (but I repeat myself) avoid this type of writing and thinking at all costs. Ehrenreich made a career out of exposing the hollowness at the core of the American Dream myth — using anecdotal evidence (often hands on) to illustrate the vast gulf between what we’re sold and what we swallow. She is part of a distinguished through-line of cultural icon –equal part muckraker and raconteur– that connects thinkers as diverse and essential as George Orwell and Anthony Bourdain.

“The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.” — George Orwell

“Everything important I learned, I learned as a dishwasher.” –Anthony Bourdain

A lot more on dishwashing and the dignity of hard work, here.

I’m not certain if it has anything to do with what you study in college, or the type of person you already are (of course the two are not mutually exclusive by any means) but speaking for myself, I suspect that if you are a certain age and not already convinced that God is White and the GOP is Right (and anyone under the age of twenty-one who is certain of either of those things is already a lost cause, intellectually and morally), reading a book like Down and Out in Paris and London changes you. Reading a book like The Jungle changes you. Books like Madame Bovary change you. Books like The Second Sex change you. Books like Notes From Underground change you. Books like Invisible Man change you. Books like Nickel and Dimed change you. Then you might start reading poetry and come to appreciate what William Carlos Williams meant when he wrote “It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” These works alter your perception of the big picture: cause and effect, agency vs. incapacity and history vs. ideology.

Put another way, even if you are open-minded and receptive to various sources of information, if your studies focus on economics, business or political science you are already being inculcated into an established way of thinking. Liberal arts education, if it has anything going for it (and it has plenty, actually), reinforces and insists upon what Milan Kundera called a “furious nonidentification”. This does not mean to imply that all, or most, or even some of the students who embrace (or abscomb from) the ivory tower remain inquisitive and objective. It does mean that reading works from different cultures and different times inevitably denotes truths and facts (even if couched in fictional narratives) that are outside of time and agenda.

It is, therefore, easier then to make connections between Irish immigrants who worked the coal mines in Pennsylvania and Lithuanian immigrants who worked in the meatpacking plants in Chicago (Jurgis Rudkus, anyone?) and Mexican immigrants –especially the illegal ones– who labor in sweltering kitchens and frigid fields all across our country. It is impossible not to put human faces and real feelings alongside this suffering and start connecting the dots that define how exploitation works. All of a sudden, it’s less easy to espouse the impartial axioms of the Free Market and the immutable forces of commerce or especially the notion that (in America anyway) everyone starts out at the same place and those that work hard enough and say their prayers and drink their milk will attain vast fortunes without breaking laws, stepping on innocent faces and engaging in the oppressive pas de deux with Power (and the puny but influential people who possess it). Then, presumably, it goes from being merely disconcerting to outrageous that the weasels of Wall Street are back in business with billion dollar bonuses (thanks tax-payers!) and unionized public school teacher pensions (and the immigrants providing so much of this industry, and revenue) are being blamed for America’s current deficits.

***

Additional and occasionally amusing reminiscences of my blue collar experiences, here.