Listen: hearing is believing. Always. Which isn’t to say that we don’t need or shouldn’t appreciate critics (hi!), but sometimes it really is best to let the tape roll and have the art account for itself. If you get it, you get it, if you don’t, keep trying or…maybe peak human achievement via creative expression simply isn’t your bag. Different strokes for different folks, like the man said.

Right?

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This isn’t merely pop perfection. Or the unfettered expression of an absolute genius. Or a short, affirmative statement that becomes a definitive cultural document, nailing an era and the hope that accompanied everything the squares (then, now) stood against. It was all those things. But it’s Sui generis: it’s a whole vocabulary, a blueprint for how to do something fresh and new, even though, after one listen, it’s obvious no one could copy this—though many have tried (then, now). This is like a sculpture that has been painstakingly crated and shaped from a large, formless chunk of marble, reduced to its absolute essence, not a superfluous second or note, and it’s within this compression we might wrap our heads around the discipline, the years of trial and error, the lessons learned, the cultivation of an original voice, the myriad influences, and that once-in-a-generation ability to ascertain which way the wind’s blowing before it blows, indeed, becoming the force of nature that blows it in the right direction. All of this. And while thousands of words could be written—and have been, obviously—trying to articulate what’s going on…it just has to be heard to be believed. It’s at once untouchable and right in front of your face: that’s the mystery and bliss of certain types of genius. We may not be able to adequately describe or understand it, but we know it when we hear or see it.

(LISTEN TO THE VOICES!)

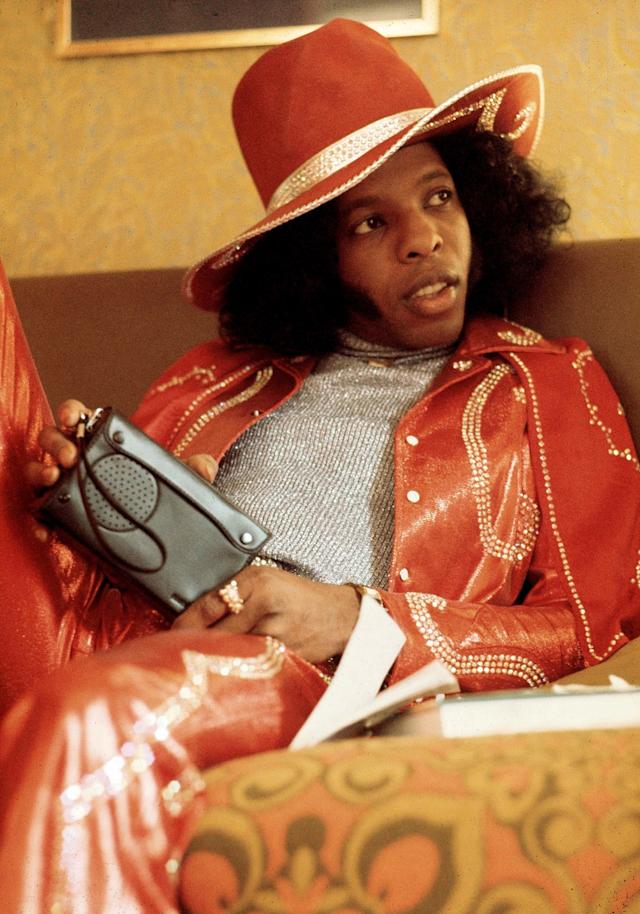

Sly Stone was a genius. And for once (unlike so often when a writer or musician—especially my beloved jazz heroes—pass and I feel I need to throw my hat in the ring to bear witness), there are plenty of capable folks detailing the career and the many bright moments, so I encourage anyone who isn’t already well-versed to seek out the obits and then go back to the grooves, revisiting or, if you’re so fortunate, exploring for the first time, all this glorious stuff.

Listen:

Inimitable. Untouchable. Perfect.

And if Sly had shuffled off, a self-indulgent O.D. or car crash or thinking man’s Jim Morrison—splitting to live off royalty checks and cocaine in Paris or Rome or Laurel Canyon, he would be a spotless idol, a saint, a martyr. He would have been less mysterious, easier to pinpoint, more agreeable to the accustomed script.

Of course he had more to give, more to live. He had to suffer, go deeper (way, way deeper) inside himself, and like no artist aside from Syd Barrett, document what it was like to be at once within one’s own mind and catapulted into the farthest, darkest places beyond this planet.

Could it be more appropriate, more portentous, more perfect, that “Everybody Is a Star” dropped—as a single—in December 1969?

For me, this song neatly (and, yes, perfectly) cuts the before/after like a razor blade through an onion—an onion that’s going to spice things up and trigger all sorts of unwanted chemical reactions. I could think of some contenders, but I’m not sure I could find a more crystalline instance of a song that manages to be ebullient, celebratory, and triumphant (not just a song of oneself, but an actual call to arms, a reminder that we all matter, that everyone is someone), but hint (inevitably? intentionally? unintentionally?) at the darkness around the corner, the coming desolation, the hangover after all the peace, love, happiness. (Arthur Lee left us his own indelible observations from the trenches with Love’s Forever Changes.) Many turned on, tuned in, and dropped out. Some, like Jimi, Janis, and Jim, dropped out altogether; others, like Syd and Sly, dropped down into a hole even they couldn’t fathom or find their way out of. And they put it on the permanent record.

Listen: I was an English major. Better still, a grad student who enjoyed lit criticism. I am, in other words, a hopeless case and always was. I can appreciate that, via textual analysis, knowing what happened in the ‘70s (and pretty much for the remainder of his weird, haunted life) indelibly colors perception of a song like “Everybody Is a Star.” Still…I hear it in those choruses. Those “ba ba ba bas” very different than the a cappella “Dom Dom Dom Doms” that make “Dance to the Music” so blissfully irresistible.

Maybe this was a soundtrack of the high-water mark Hunter S. Thompson describes (for me, the definitive take on how the ‘60s Dream turned, in many ways, into the American Nightmare of the ‘70s—and beyond, a war eagerly fought by conservatives to undo every bit of peace & progress people fought and died for during that complex and monumental decade): We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave…So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back. (A lot more on this, and how art in the ‘70s reflected this reality, here.)

Listen: even this manages to move the right muscles, convey something like happiness, possibly make those who know how to dance do so. But it’s undeniably the thunder rumbling in the near distance, warning us to head for cover because a hard rain’s about to fall. Listen to 2:50 and it’s not simply obvious things have changed since 1969, this is a whole other human being making these sounds.

You can (and should!) read about the circumstances under which this brooding, mournful masterwork was recorded, but fortunately, we can listen and understand as much as is necessary: the revolutionary use of a drum machine, the gleeful insanity, and this—a love letter left out on the table before the host checked out and dealt with himself behind closed doors for a few hours or decades.

Listen: it’s all here.

(And listen to Vernon Reid, the only musician who could conceivably go there, and do it justice in his way.)

Improbably, impossibly, Sly not only wasn’t done, he had gifts to deliver that were as brilliant and inscrutable as anything he’d already done.

Listen:

Listen:

If you want me to stay

I’ll be around today

To be available for you to see

But I am about to go

And then you’ll know

For me to stay here, I got to be me…

I’ve read many times that people who get addicted to hard drugs are forever chasing the feeling they got from that first high; the more they try, the more desperate they become, and inexorably the drugs drain wallets, end careers, kill families, and sap both passion and purpose. There’s more than a little irony that Sly Stone, who has been described over the decades as everything from tragic cautionary tale to joke, left documents that do what only the best art achieves: it gives you that initial, impossible high, then subsequently delivers, every single time. This is that narcotic effect with all the best aspects and none of the negative. One of the many reasons I’d never dare judge Sly (or his ilk) is that his gift—and this world—took so much from him, and he sprinkled life-affirming miracles all over the world for us to savor and enjoy, forever. All I can and will offer him is every bit of awe and gratitude I’m capable of extending. Sly Stone, like any individual, contained multitudes, but he accomplished what an exceedingly small and distinguished company of human beings did: he provided a delivery device for bliss.

Go read the bios and tributes (and definitely see as much video as is available, with a definite nod to the sublime documentary courtesy of Questlove & Co.—including the aforementioned Vernon Reid—more on him here.)

I’d not written too much about Sly, mostly because many qualified scribblers had documented him and his music. I was—and remain—more interested in that darkness, the creative, cultural, and societal pressures that produced such a diamond of mirth, magic, and madness. The Man, his method & madness, are right there, in black and white; try to touch it and there’s nothing there. I did my best to use as few words as possible to appraise this mountain of energy and ecstasy, and go a bit deeper into myself to capture something unique.

Sly Stone’s Star

Everybody is a star, you said—but anybody

can tell that some stars shine more brightly.

Family affairs and everyday people—stand

or float away, a spaced cowboy making small talk.

Speaking of space: what are you left with when

you have more in common with aliens (only you

can see)—and nothing of substance to exchange

with see-through civilians who talk like TV sit-coms?

You could make it and you tried, blowing a short

cut into the earth’s boring core, seeking black holes

that might comprehend your holy blackness; space

just another stage where The Sun holds court—daring

anybody to come too close—and ready to return all

the brazen ones to this cold world, burned out shells:

broke and without options—now obliged to pay cash

for one-way tickets to other planets of their choosing.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On*

(*Sly Stone intended to name his 1971 album Africa Talks to You but changed it to There’s a Riot Goin’ On as a response to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, released earlier that year.)

It’s that rainy day on his album cover, Marvin grim

but game to assess the contentious state of our union,

filtered through his own pains and pitfalls, always

able to perceive the sun skulking behind the clouds,

neither optimism nor acceptance: a sensibility shaped

by countless church sermons and street scenes; seeing

the goodness of exploited people trying to get over,

feeling flames closing in from all sides—America

a melting pot that takes the heat, absorbing ingredients

flavored with Luv N’ Haight, but also Hope: we dug

this grave but can dig ourselves out, Everyday People

with a prayer and the hope: I Want to Take You Higher.

I’ll tell you What’s Going On, a face from our future says:

the American flag w/ spaced out stars, suffocated by its own

aberrations, one loved child learning while another burns,

boys with bricks in their backyards sent into dark jungles

to reclaim the prizes empires always pay for, a subscription

that re-ups until peace time; then we get busy building

prisons to keep invisible men on the back burner, simmering

and setting their sights on one another, like so many bugs

trapped in a bottle scorching under the search lights, praying

for some rain to wash away the sins and this smell—Death

just a shot away and Time here to stay, like snow-blind poets

lost inside themselves, scarcely believing the things they see.

The two poems, above, appear in my collections Rhapsodies in Blue and Kinds of Blue. Buy them here.